Weiqi (ΧÆå)

Weiqi (a.k.a. "Go" in Japanese) is a wonderful ancient Chinese game for two players, superficially similar to "Othello" but much, much richer in 'phenomenology'. The reason for the richness of Weiqi is two-fold: first, the rules are incredibly simple (black and white take turns placing "stones" on a grid, capturing" any opponent's stones which are thus surrounded) while the game space is large (the board is a 19 x 19 grid, so there are at least 361! > 10^724 = 1,000,000,000,....000 (that's 724 zeros!) possible distinct games), much larger than Western chess, which has comparatively complicated rules on a much smaller board. Surprisingly, weiqi enjoys a lesser international reputation than chess, but this is bound to change as more and more people become "enlightened."

I have studied weiqi on and off for ten or more years, at one time achieving an amateur rank of 2-dan (see my certificate here), which is like a "second-degree black-belt." Actually there is a semi-quantitative measure of one's rank, which goes like this: the numerical difference in levels is roughly equal to the number of moves 'headstart' the stronger player could allow, and just break even in score. So a 4-dan could let me first place two stones anywhere on the board before he moves, and then the game would be pretty even-matched. But if he let me place three or more stones, I should have the advantage the whole game and eventually win, theoretically. This ranking system works (there are also 30 levels below that of 1-dan, to include beginners of all strengths) but since it's only a relative scale, it tells you nothing about the absolute strength of players. In fact, as more people play and devote time to studying weiqi, developing the state of the art, the definition of "1-dan" keeps getting stricter all the time. And the players keep getting younger, too! When I eventually get around to getting 3-dan, I'll probably have to compete with a room full of 8-year-olds throwing paper wads at me, a challenge unto itself!

But aside from just being a "game" (or, as many would agree to, a philosophical system), weiqi is also a "playground" for considering physical theories on a discrete space. Indeed I went a bit wild with this idea in an interview which "The World of Weiqi" (a Beijing magazine) below did with me.

|

|

|

|

|

English translation below:

Physics ¡ñ Weiqi(Go)

Professor Ke Jia-Hua (Nicholas Kersting) graduated in 1997 from Carnegie-Mellon University, got a Ph.D. in Physics at U.C. Berkeley in 2002, and now teaches in the Sichuan University Physics Department. He has published a number of papers and represented work at international conferences. Fluent in Russian and Mandarin Chinese, his hobbies include Weiqi, Wushu, Calligraphy and Fine Arts.

Our editorial office was taken by surprise today when Wang Yuan (8-dan) brought his ¡°home-town friend¡± Dr. Nicholas Kersting through the door. Though American by birth and European in descent, he may indeed by Chinese standards qualify as a native of Chengdu. Known here by his Chinese name, Ke Jia-Hua, and presence as faculty in the Physics Department at Sichuan University, Dr. Kersting's enthusiasm in Chinese culture and fluency in Mandarin arouse either admiration or shock from locals, depending on whether or not they know whom they're talking to. Of course these days foreigners particularly well-spoken in Chinese are not so difficult to find, and the present interview is not concerned with Dr. Kersting's linguistic abilities, but rather with his insights into wei-qi (go) from the viewpoint of modern physics.

Dr. Kersting's introduction to wei-qi bears the mark of legend, or perhaps of some movie we might have seen, keeping in mind of course that real life is vastly richer than words in books or what can be shown on the silver screen. He encountered wei-qi over ten years ago, while was working on his Ph.D. at U.C. Berkeley. As it happened, in his spare time he and his friends would get together to organize meals for the homeless people that routinely gathered in People's Park, and it was there that he met a drifter who, like other visitors to the Park, surfaced to fill up on whatever was being given away for free, before diving back down into the mysterious waters that are the lives of Berkeley `wing-nuts'. In this drifter's case, the rest of the day was spent playing wei-qi at the local Go Club. Now to some people, there is nothing unusual in `killing time' on a game between meals, but to Dr. Kersting, who from an early age took a keen interest in Eastern culture, the impression was different: here was someone living on another plane of awareness, unbound by standard rules of society in pursuit of one strict and highly meaningful discipline. Dr. Kersting informally started studying wei-qi with this `Master,' or perhaps ¡®Drunken Master' judging by his game record: at times he would beat very strong players, but he would also routinely fail in the most embarrassing ways against beginners. This method of discovering wei-qi was a major event in Dr. Kersting's life. The game not only offered a fascinating object of study, but also inspired new ideas in his professional career.

What is the relation between physics and wei-qi, then? Nobody who understands even a little of each can deny the two are connected. Physics is essentially the union of geometry and logic; its goal is to use the least number of simple, fundamental rules to describe the largest number of complex natural phenomena. The rules of wei-qi are indeed simple: each black or white stone is alternately placed on the intersection of two lines on the board, and when `liberties' (unoccupied points on stones' perimeters) are exhausted, the surrounded stones are removed. It's that simple. But the resulting number of ensuing combinations and phenomena are mind-boggling: as Dr. Kersting says, even if you started playing wei-qi from the beginning of the universe (13 billion years ago) and played a game every second, you would at present not even have exhausted the tiniest fraction of the total number of distinct games, a heartening fact for those of us who make a profession out of wei-qi.

But, he goes on to say, enormous as the wei-qi `system' appears, it utterly pales in comparison to even a small everyday physical system such as a child's ferromagnet, where the sheer number of interacting spins gives rise to dynamics too complicated to even express in words (hence the physicist's resorting to average variables such as temperature and entropy in discussing such objects). Clearly, he states, the standard 19x19 wei-qi board cannot seriously represent a real physical system. ¡°We are large-system experts, while wei-qi players are small-system experts.¡± The room sighs: wei-qi, as complex as our brains make it to be (it can take many decades just to reach 5-dan), is from a cosmic standpoint but some infinitesimal scrimshaw. What interest would a physicist possibly have in it then? The magic thing, Dr. Kersting says, is that although wei-qi is a `small system' from a physical standpoint, it nevertheless embodies a host of fundamental physical concepts, many of which belong to the realm of modern physics and which have yet to be fully understood by scientists. Take for example the concept of ¡°fine-tuning.¡± In wei-qi we have the expression ¡°extend one liberty for life,¡± applying to a general strategy for shape; a group of stones, regardless of how large it is, only survives if it has two `eyes' (internal holes). In Dr. Kersting's words, this topological fact nicely demonstrates ¡°the very small affecting the very large.¡± Of course, to a wei-qi player that's as natural as can be, but to most modern physicists this way of thinking is unusual and ¡°unnatural.¡± In the perfect world, most physicists would say, the very small and the very large should be decoupled from each other. Ironically, however, elementary particle physics is full of `embarrassing' hierarchies: the heaviest known quark (the ¡°top¡±) for example, is 30,000 times heavier than the equally fundamental electron.

At this point, Wang Yuan interjected: could not wei-qi then be the perfect world? After all, it is orderly and symmetric. In reply, Dr. Kersting answered that, yes, the wei-qi board is initially perfect and symmetric, but once play commences this symmetry is lost, or, in physicists' jargon ¡°the symmetry is spontaneously broken.¡± A good example of this is violation of the Go adage ¡°In a symmetric position, play in the middle.¡± Dr. Kersting, in passing, gave us two examples (one from a life-death problem book, and one he thought up himself) of left-right symmetric configurations where the next correct move was not in the middle, giving Wang Yuan a little revelation. Symmetry-breaking is a major modern physics problem which routinely appears in various guises: the asymmetry of the stars and galaxies, matter and anti-matter, and masses of elementary particles, to name a few instances. We tend to think things should be symmetric, yet Nature, paradoxically, does not ever seem to favor perfect symmetry, a fact you can easily convince yourself of by comparing a photo of yourself with its mirror image. In wei-qi, the initially perfectly symmetric board gets `broken' as stones are put into play ¡ perhaps wei-qi is after all a god-given laboratory in which we can study the world.

Unfortunately, modern physicists don't know how to use this laboratory, or often don't know it exists. This, Dr. Kersting says, is something of a tragedy for those people. They have never seen a black stone placed in the lower right corner, suddenly joined by a white one, black, white...quickly exploding into a roiling life-and-death battle where every move erupts into dozens of more variations that put your nerves into overdrive. But, from a distance, we have the sober fact that the outcome of this struggle has probably already been decided by the ever-distant upper left corner, where either a white or black stone awaits to make or break a `ladder'(a sort of repeating diagonal sequence). To an experienced wei-qi player it is hardly worth mention that distant stones affect each other, but to a physicist the fact that widely separated situations can influence each other seems anti-intuitive. This is because we've gotten accustomed, in one way or another, to Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity, which implies that sufficiently far away objects cannot affect us because no signal can travel faster than light. However, already some physicists are doubting this; maybe something can go faster than light, and if so that gives us plenty to think about for the 21 st century. Dr. Kersting believes such a revolution against Einstein's theory is quite likely, even inevitable. Physics depends upon the pillar of mathematics, yet modern physics, surprisingly, leans almost solely on techniques developed in Newtonian times, embarrassingly backwards by modern mathematical standards. How high the pillar is determines how far Man may see by standing upon it, and physicists' out-dated mathematics confines them to see the world as no more than a continuous `pudding' of a spacetime; yet the world cannot be absolutely continuous --- at some level it should be discrete like a wei-qi board. If only we make this supposition, many problems of modern physics can quite possibly be resolved; however, it remains to this day a virtually unexplored topic. Dr. Kersting says that, in the most optimistic scenario, we can expect a major physics revolution in about 10 years, and the nature of this truly New Physics is probably already hinted at by wei-qi.

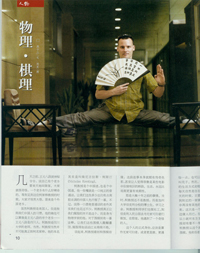

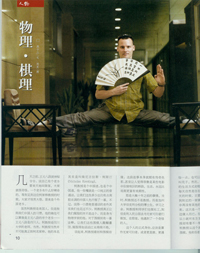

As our discussion wound down, the camera man asked Dr. Kersting for a few poses (see cover¡ Dr. Kersting had studied wushu with a Beijing Wushu Team member for 3 years, specifically learning some Taiji, Southfist, and even doing some kungfu acting). The fan he holds also has a story behind it: it is a thank you gift to Jin Qian-Qian for her teaching and guidance, depicting orchid grass and four columns of characters, all done by his own hand. Since Dr. Kersting's father is an artist, he took to drawing from an early age, and, as the Chinese saying goes, `one road leads to all roads,' it's no surprise he's taken to Chinese painting and calligraphy as well. The words he had chosen to write on the fan are of particular significance:

One emptiness is the same as two,

And includes all countless forms,

If you see neither thick nor thin,

Can it really be one or the other?

These four lines (his translation) are taken from the Chinese Zen master Seng Can's ¡°Xin Xing Ming¡± (Song of the Truthful Mind), a pivotal text for Zen Buddhists. Dr. Kersting finds them intriguing for their physical interpretation in quantum mechanics; indeed, he has often entertained his students at Sichuan University on the last day of class by reciting the Xin Xin Ming from memory, followed by an explanation of its possible physics meaning.

In this world of countless things, all must eventually be connected. What Prof. Ke Jia-Hua studies is, truly, this.